Project

Reading Faces in Milliseconds: AI for Micro-Expression Recognition

March 2024

The Emotions We Try to Hide

When someone asks how you are doing and you say “fine” while suppressing frustration, your face might betray you. Not through an obvious grimace, but through a micro-expression: a fleeting, involuntary facial movement lasting between 65 and 500 milliseconds. Blink and you miss it. Literally.

Micro-expressions occur when we try to conceal our genuine emotions, whether due to social norms, professional settings, or cultural expectations. Unlike the macro-expressions we consciously display, these brief flashes are remarkably honest. They reveal what we actually feel before our conscious mind can intervene.

This makes micro-expression recognition valuable for applications ranging from law enforcement (detecting deception) to clinical diagnosis (identifying depression or early Parkinson’s disease) to human-robot interaction (enabling robots to respond appropriately to human emotional states). The challenge is that even trained experts struggle to reliably detect these expressions through visual observation alone. They are simply too fast and too subtle.

A friend and I worked on this problem as part of a seminar and practicum at the Intuitive Robots Lab at KIT. We surveyed the state of the art in micro-expression recognition, implemented two promising approaches, and evaluated them with a focus on both accuracy and explainability. This post summarizes what we learned.

What Makes Micro-Expressions So Hard

To understand why micro-expression recognition is difficult, consider the differences from regular facial expression recognition:

| Characteristic | Macro-Expressions | Micro-Expressions |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 0.5 to 4 seconds | 0.065 to 0.5 seconds |

| Intensity | High muscle movement | Subtle, low intensity |

| Control | Consciously controllable | Involuntary |

| Perceptibility | Easily noticed | Often overlooked |

| Available data | Many large datasets | Limited, small datasets |

The brevity and subtlety create technical challenges. You need high frame rate video (100-200 fps) to capture the expressions at all. The muscle movements are so slight that traditional computer vision methods struggle to detect them. And the available datasets are small, typically a few hundred samples, because collecting spontaneous micro-expressions in a lab setting is difficult.

The seven universal emotions identified by Ekman (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, disgust, contempt) manifest differently at the micro level. A micro-expression of disgust might involve only a slight nose wrinkle lasting a tenth of a second. Distinguishing this from a micro-expression of anger, which might involve a brief eyebrow furrow, requires extremely fine-grained analysis.

The Evolution of Recognition Methods

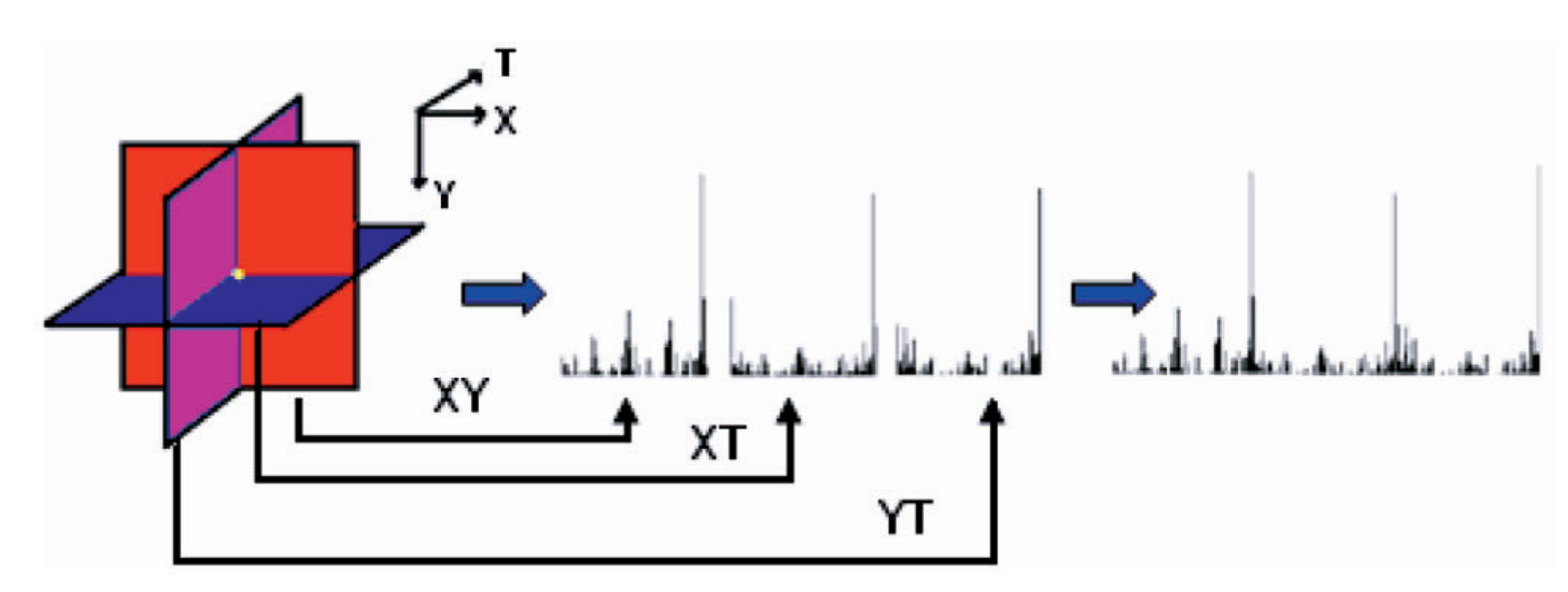

Early approaches to micro-expression recognition relied on hand-crafted features, particularly Local Binary Patterns on Three Orthogonal Planes (LBP-TOP). This method analyzes texture patterns across three dimensions: the spatial XY plane of each video frame, plus the XT and YT planes that capture temporal changes. You compute histograms of binary patterns in each plane and concatenate them into a feature vector for classification.

LBP-TOP and its variants (like LBP-SIP, which reduces redundancy by focusing on six intersection points) were the workhorses of early micro-expression research. They are interpretable since you can trace exactly how the features are computed, but their performance plateaued. On benchmark datasets like CASME II and SMIC, LBP-TOP achieves around 40-42% accuracy, which is better than random guessing but far from practical utility.

LBP-TOP processing flow: binary patterns are extracted from three orthogonal planes (XY, XT, YT) and concatenated to form a descriptor of texture dynamics.

LBP-TOP processing flow: binary patterns are extracted from three orthogonal planes (XY, XT, YT) and concatenated to form a descriptor of texture dynamics.

The shift to deep learning brought significant improvements. Convolutional neural networks can automatically learn relevant features rather than relying on hand-designed descriptors. But standard CNNs face two problems for micro-expression recognition: the datasets are too small to train deep networks from scratch, and the models operate as black boxes, making it hard to understand why they classify expressions as they do.

This is where our work focused: methods that achieve high accuracy while maintaining some degree of explainability.

Approach 1: Micro-Attention on Residual Networks

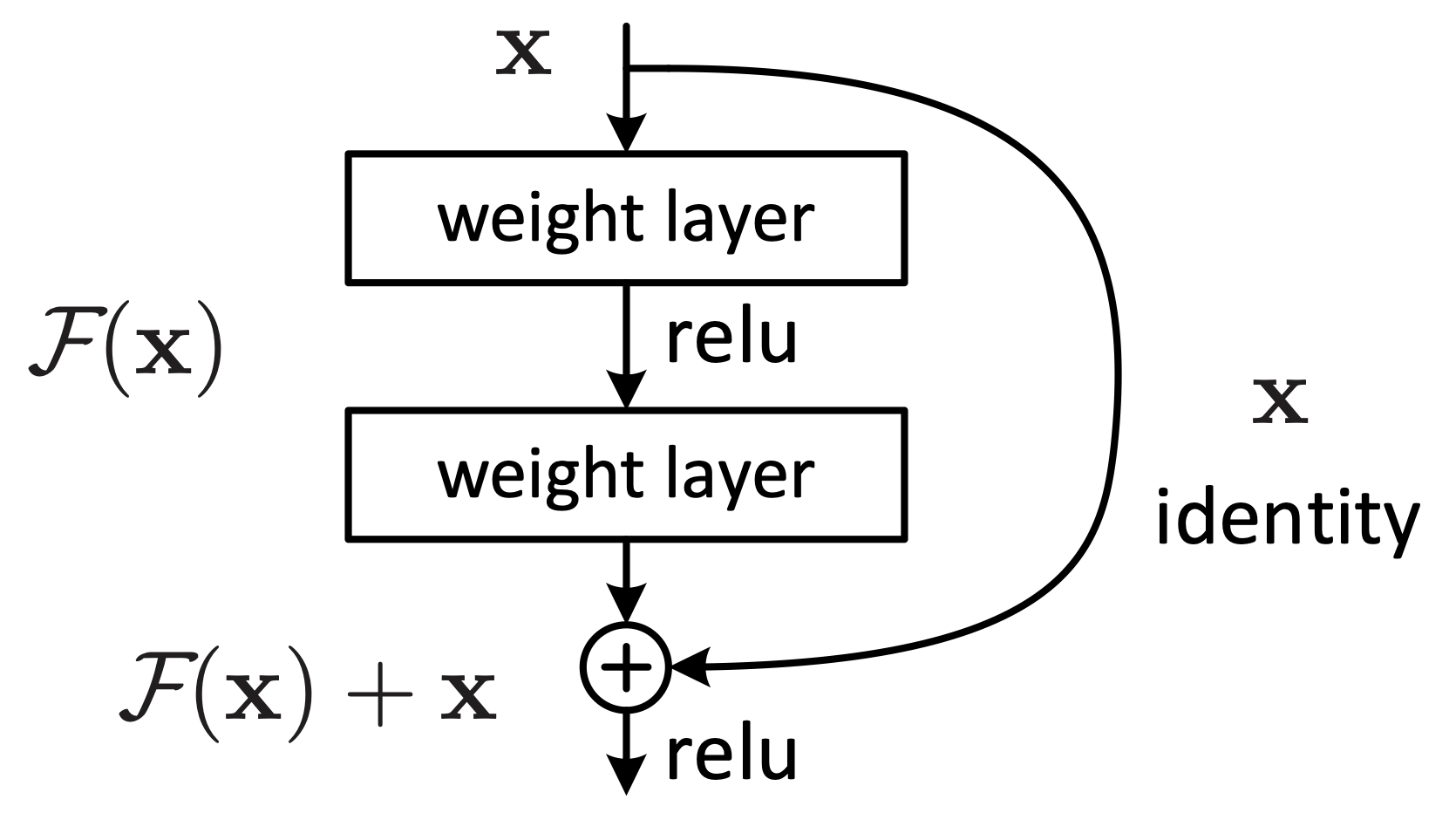

The first approach we implemented adds attention mechanisms to residual networks. The core idea is that not all parts of a face are equally important for recognizing a micro-expression. The subtle movement around the eyes or mouth matters far more than the background or hair. An attention mechanism lets the network learn to focus on the regions that matter.

A classic residual block with a shortcut connection. If a layer underperforms, it can be bypassed via the shortcut, guaranteeing performance at least on par with the preceding layer.

A classic residual block with a shortcut connection. If a layer underperforms, it can be bypassed via the shortcut, guaranteeing performance at least on par with the preceding layer.

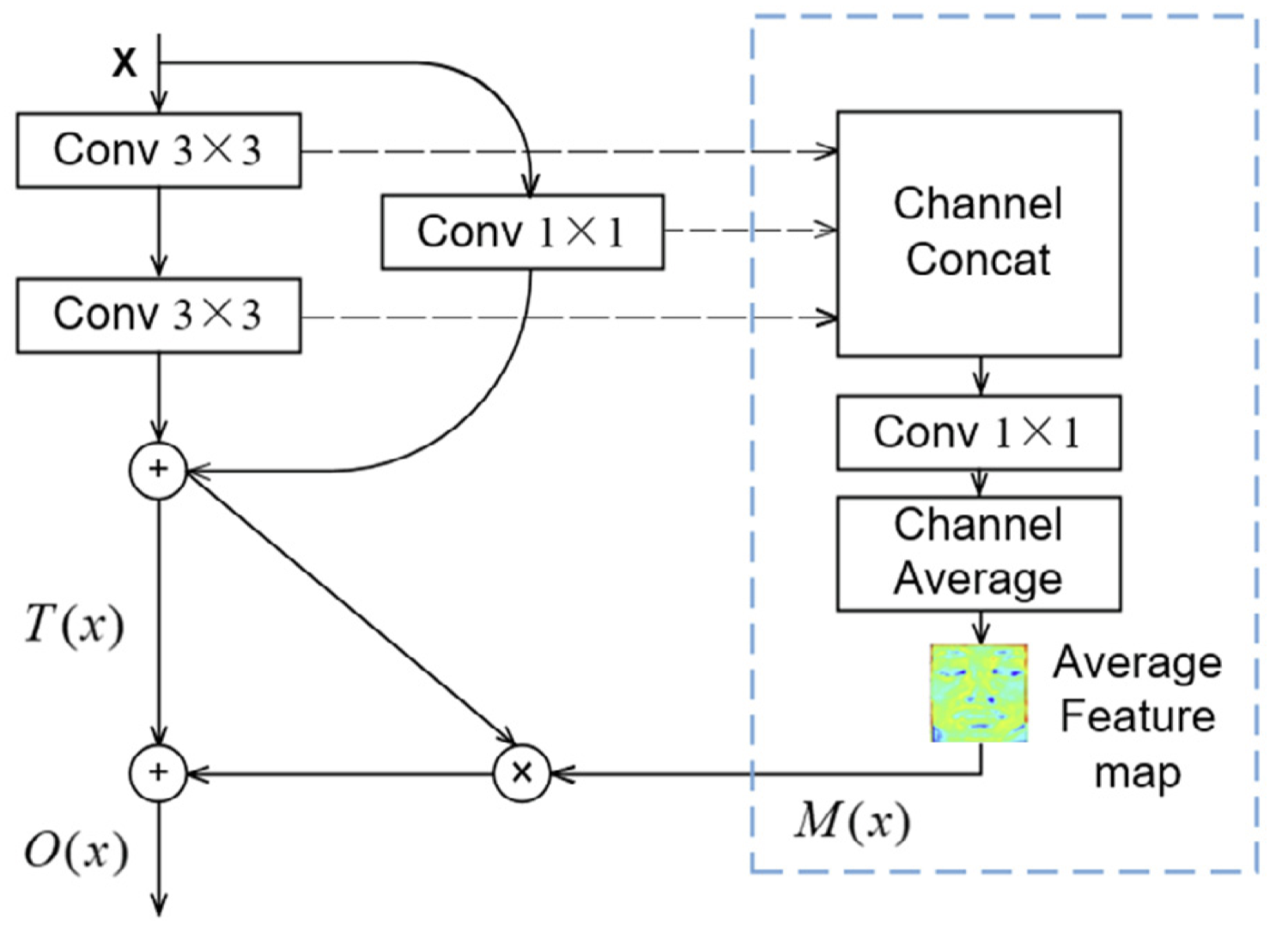

How it works: We start with a ResNet-18 pretrained on ImageNet. Within each residual block, we add a micro-attention unit that computes a spatial attention map. The unit takes feature maps from multiple convolutional layers, concatenates them, applies an embedding layer, and averages across channels to produce a single attention map. This map is then multiplied element-wise with the residual output, amplifying important regions and suppressing irrelevant ones.

The mathematical formulation is straightforward. For input X, the three convolutional layers in a residual block produce feature matrices that get concatenated and passed through an embedding layer. Channel-wise averaging produces the attention map M(X). The final output combines this with the residual output T(X):

O(X) = T(X) * [1; M(X)]

A micro-attention unit (within the dotted area) integrated into a residual block. The unit learns spatial attention maps that highlight important facial regions.

A micro-attention unit (within the dotted area) integrated into a residual block. The unit learns spatial attention maps that highlight important facial regions.

Transfer learning: Since micro-expression datasets are small (a few hundred samples), training from scratch would lead to severe overfitting. Instead, we freeze the pretrained ResNet weights and only train the attention units. This dramatically reduces the number of parameters to learn while leveraging features already learned from millions of ImageNet images.

Explainability via Grad-CAM: One advantage of this architecture is that we can apply Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to visualize what the network focuses on. Grad-CAM computes the gradients of the classification output with respect to feature maps in the final convolutional layer, producing a heatmap showing which image regions contributed most to the prediction.

Our Grad-CAM visualizations showed strong activation in the eye, mouth, and nose regions, confirming that the model focuses on facial features relevant for expression recognition. However, some images also showed activation in background regions, suggesting potential overfitting to contextual cues.

Approach 2: Prototype Learning with Autoencoders

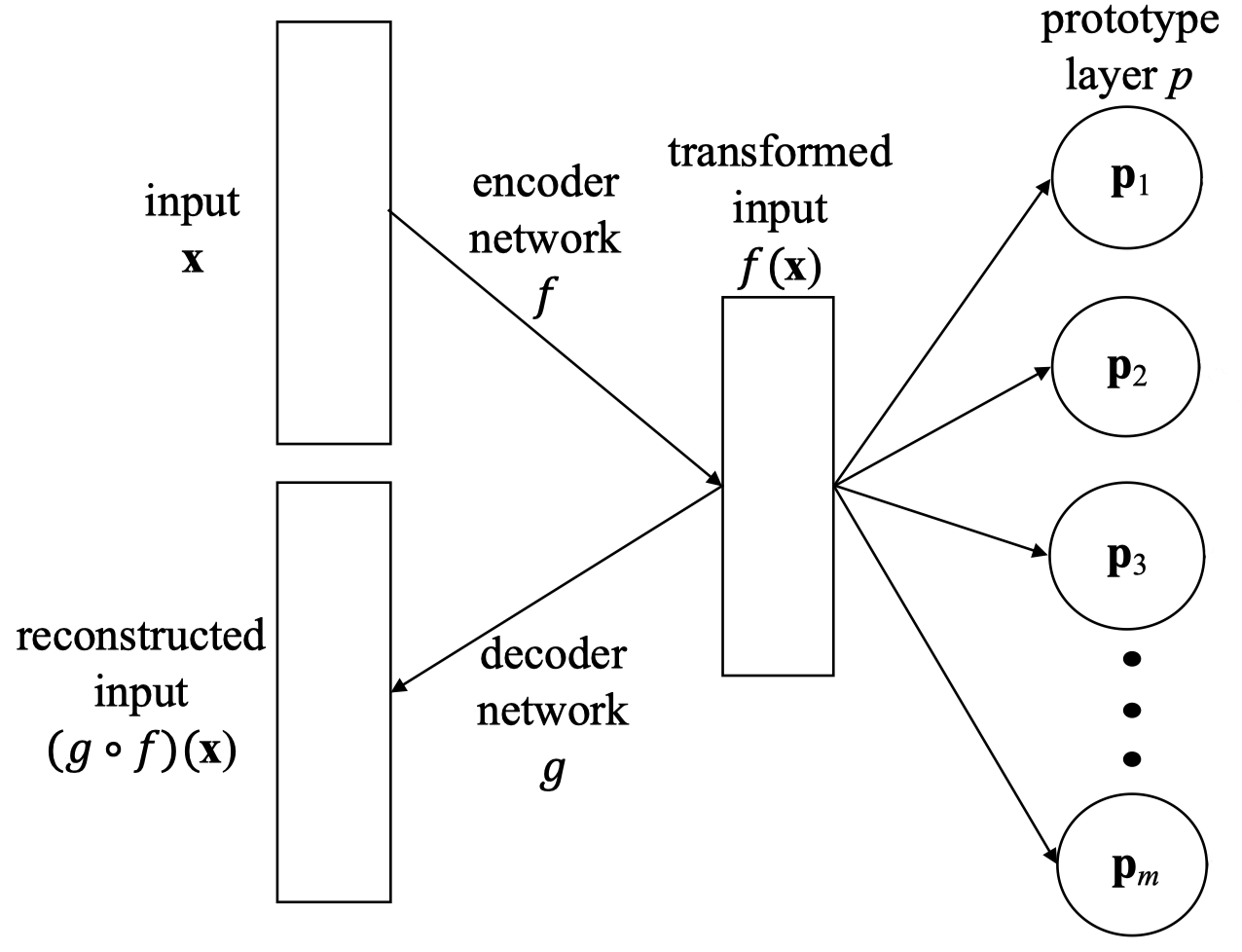

The second approach aims for deeper explainability through prototype learning. Instead of just highlighting important regions, this method learns representative examples (prototypes) for each expression class. Predictions are made by comparing new inputs to these prototypes, and the prototypes themselves can be visualized to understand what the model has learned.

Architecture: The network combines an autoencoder with a prototype classifier. The encoder (a ResNet-18 without the final layer) compresses input images into a 512-dimensional feature vector. This vector is passed to a prototype layer containing one prototype per emotion class. Classification is based on the squared L2 distance between the encoded input and each prototype.

Prototype-based network architecture combining an autoencoder with prototype learning. The encoder compresses input to a latent representation, which is compared to learned prototypes for classification.

Prototype-based network architecture combining an autoencoder with prototype learning. The encoder compresses input to a latent representation, which is compared to learned prototypes for classification.

The decoder reconstructs the original image from the encoded representation. This serves two purposes: it regularizes the encoder to learn meaningful features, and it allows us to decode the prototype vectors back into images, visualizing what each prototype represents.

The loss function: Training optimizes four terms simultaneously:

- Classification loss: Standard cross-entropy for correct predictions

- Reconstruction loss: L2 distance between input and reconstructed image

- Cohesion loss: Encourages each prototype to be close to data points of its class

- Separation loss: Encourages data points to be far from prototypes of other classes

The cohesion and separation losses guide the prototypes to become meaningful representatives of their classes rather than arbitrary points in feature space.

Visualizing prototypes: After training, we can decode each prototype through the decoder network to see what it represents. In our experiments, prototypes decoded after 10 epochs contained many black spots and unclear features. After 50 epochs, the decoded prototypes looked more like recognizable faces, though still somewhat abstract. This progression reflects the learning dynamics: early in training, the model prioritizes discriminative features for classification; later, it refines its understanding to produce more realistic reconstructions.

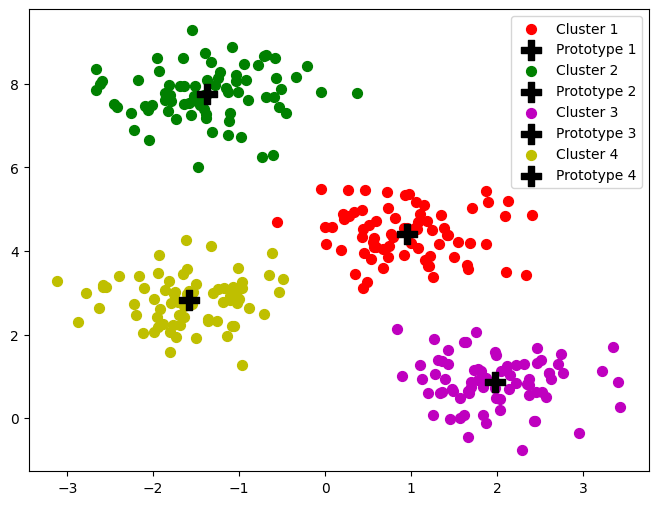

K-Means clustering visualization illustrating the prototype concept. Cluster centers serve as representative prototypes for classification.

K-Means clustering visualization illustrating the prototype concept. Cluster centers serve as representative prototypes for classification.

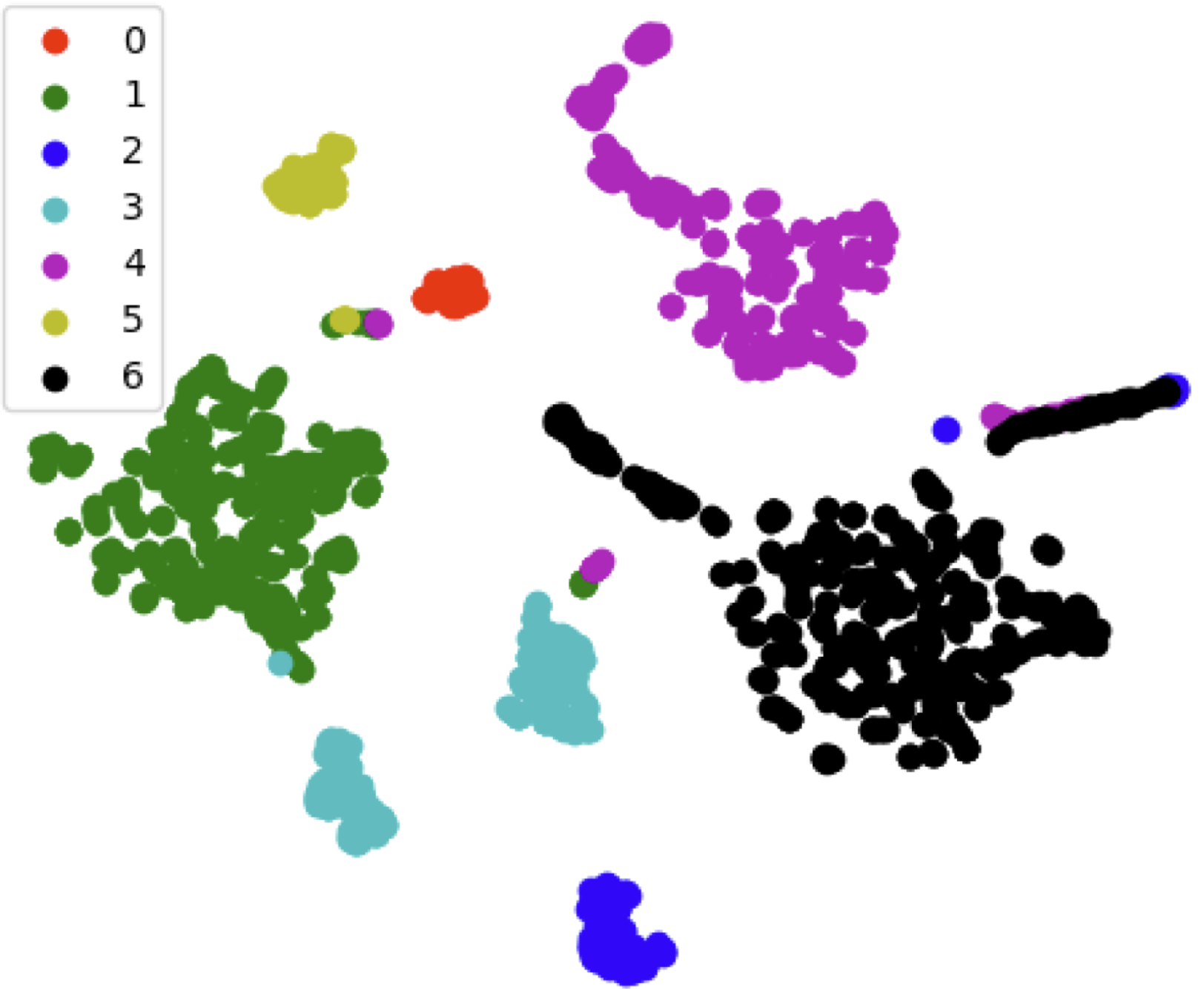

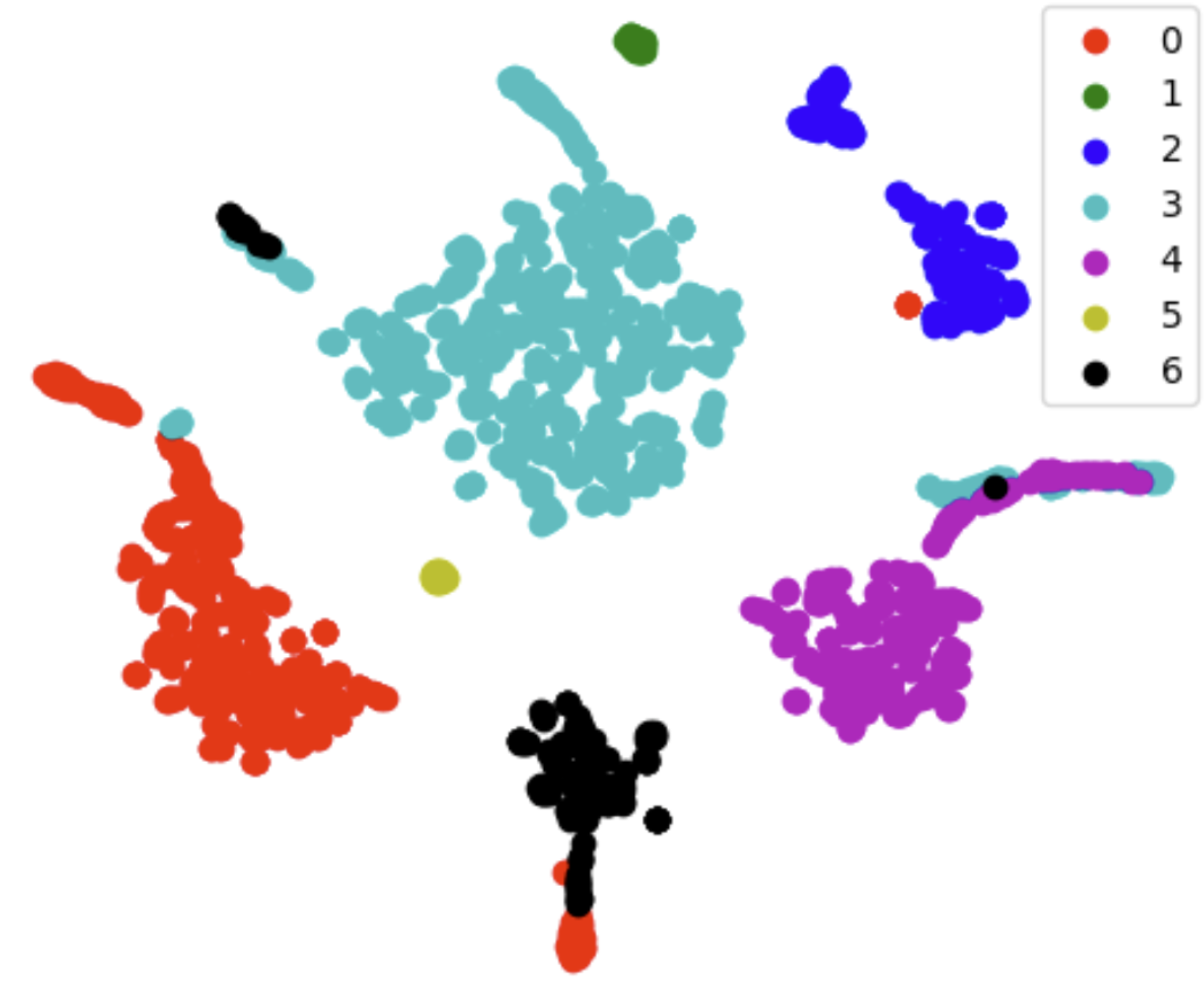

t-SNE visualization: We also visualized the learned feature space using t-SNE. The resulting plots showed distinct clusters for different emotion classes, with clear separation between most categories. Notably, the “fear” class appeared as sparse, isolated points, consistent with its rare occurrence in the datasets (only 1 sample in CASME II).

Latent space visualization for the MMEW dataset. Distinct clusters indicate good class separation learned by the prototype network.

Latent space visualization for the MMEW dataset. Distinct clusters indicate good class separation learned by the prototype network.

Latent space visualization for CASME II. The sparse yellow dots (class 5, “fear”) reflect its rare occurrence in the dataset.

Latent space visualization for CASME II. The sparse yellow dots (class 5, “fear”) reflect its rare occurrence in the dataset.

Experimental Results

We evaluated both approaches on two datasets: CASME II (247 samples, 200 fps, widely used benchmark) and MMEW (300 samples, 90 fps, newer multimodal dataset). Due to dataset access constraints, we used a 70/30 train/test split rather than the more rigorous Leave-One-Subject-Out cross-validation common in the literature.

| Dataset | Method | F1 Score (10 epochs) | F1 Score (50 epochs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMEW | Prototype Learning | 0.853 | 0.981 |

| MMEW | Micro-Attention | 0.649 | 0.982 |

| CASME II | Prototype Learning | 0.956 | 0.972 |

| CASME II | Micro-Attention | 0.900 | 0.981 |

Both approaches achieved high F1 scores after sufficient training. The prototype learning approach showed faster initial convergence (higher scores at 10 epochs), likely because the explicit prototype loss provides additional learning signal beyond classification accuracy.

However, we suspect overfitting given the small dataset sizes and high model complexity. The 50-epoch scores may not generalize well to held-out subjects or different recording conditions. Proper validation would require access to macro-expression datasets for pretraining and more rigorous cross-validation protocols.

Comparing State-of-the-Art Methods

To contextualize our implementations, here is how various methods compare on standard benchmarks using Leave-One-Subject-Out evaluation:

| Method | CASME II Accuracy | SAMM Accuracy | SMIC Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBP-TOP | 40.5% | 41.8% | 42.4% |

| LBP-SIP | 42.1% | 42.7% | 44.3% |

| Enhanced LCBP | 78.5% | 79.4% | 79.3% |

| Micro-Attention | 65.9% | 48.5% | 49.4% |

| ME-PLAN (Prototype) | 89.6% | 76.9% | N/A |

The Enhanced LCBP method, which extends LBP to capture spatial differences and temporal gradients, achieves strong performance while remaining interpretable through its explicit feature engineering. The prototype-based ME-PLAN approach achieves the highest accuracy on CASME II while also providing explainability through its prototype mechanism.

The Explainability Tradeoff

Each method offers different levels of explainability:

LBP-based methods are inherently interpretable since they apply explicit, rule-based algorithms to analyze texture patterns. You can trace exactly how features are computed. However, when combined with complex classifiers like SVMs or CNNs, the overall system becomes harder to interpret.

Micro-attention mechanisms provide visual explanations through Grad-CAM, showing which facial regions influenced the prediction. This is useful for verification (confirming the model focuses on relevant areas) but does not explain the reasoning process.

Prototype learning offers the deepest explainability. Predictions can be explained as “this expression is classified as disgust because it is most similar to this prototype,” where the prototype itself can be visualized. This mirrors how humans might explain expression recognition: by reference to canonical examples.

Challenges and Future Directions

Several challenges emerged from this work:

Dataset limitations: The available micro-expression datasets are small and often restricted to academic access. Training robust models requires more data, but collecting spontaneous micro-expressions is inherently difficult.

Evaluation inconsistency: Different papers use different preprocessing, data splits, and evaluation protocols, making direct comparisons difficult. The field would benefit from standardized benchmarks.

Generalization: Models trained on one dataset may not generalize to others due to differences in recording conditions, participant demographics, and elicitation methods. Cross-dataset evaluation should become standard practice.

Prototype selection: For imbalanced datasets (where some emotions appear much more frequently than others), having one prototype per class may not capture the true data distribution. Investigating multiple prototypes per class or adaptive prototype allocation could improve performance.

Real-world deployment: Lab-recorded datasets differ significantly from real-world conditions. Variations in lighting, camera angle, and face occlusion pose additional challenges for practical applications.

Conclusion

Micro-expression recognition sits at an interesting intersection of computer vision, psychology, and explainable AI. The expressions themselves are fascinating: brief windows into genuine emotion that bypass our conscious control. The technical challenges, small datasets, subtle signals, and the need for explainability, push the boundaries of current methods.

Our work implemented and evaluated two approaches that balance accuracy with interpretability: attention mechanisms that can be visualized through Grad-CAM, and prototype learning that explains predictions through reference to learned exemplars. Both achieved strong performance on benchmark datasets, though questions about overfitting and generalization remain.

For applications like clinical diagnosis or human-robot interaction, explainability is not optional. A robot that responds to detected emotions must be able to justify its interpretations. A diagnostic tool must explain its reasoning to clinicians. The future of micro-expression recognition lies not just in higher accuracy, but in models whose decisions we can understand, verify, and trust.

This post is based on my work completed at the Intuitive Robots Lab, Institute for Anthropomatics and Robotics, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology

References

-

Wang, C., Peng, M., Bi, T., & Chen, T. (2019). Micro-Attention for Micro-Expression Recognition. arXiv:1811.02360.

-

Zhao, S., Tang, H., Liu, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Xu, T., Chen, E., & Guan, C. (2022). ME-PLAN: A deep prototypical learning with local attention network for dynamic micro-expression recognition. Neural Networks, 153, 427-443.

-

Yan, W.J., Li, X., Wang, S.J., Zhao, G., Liu, Y.J., Chen, Y.H., & Fu, X. (2014). CASME II: An Improved Spontaneous Micro-Expression Database and the Baseline Evaluation. PLOS ONE, 9(1).

-

Zhao, G., & Pietikainen, M. (2007). Dynamic Texture Recognition Using Local Binary Patterns with an Application to Facial Expressions. IEEE TPAMI, 29(6), 915-928.

-

Selvaraju, R.R., Cogswell, M., Das, A., Vedantam, R., Parikh, D., & Batra, D. (2019). Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. International Journal of Computer Vision, 128(2), 336-359.

-

Ekman, P. (2009). Lie Catching and Microexpressions. The Philosophy of Deception, 118-136.

-

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2015). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv:1512.03385.

-

Li, O., Liu, H., Chen, C., & Rudin, C. (2017). Deep Learning for Case-Based Reasoning through Prototypes: A Neural Network that Explains Its Predictions. arXiv:1710.04806.